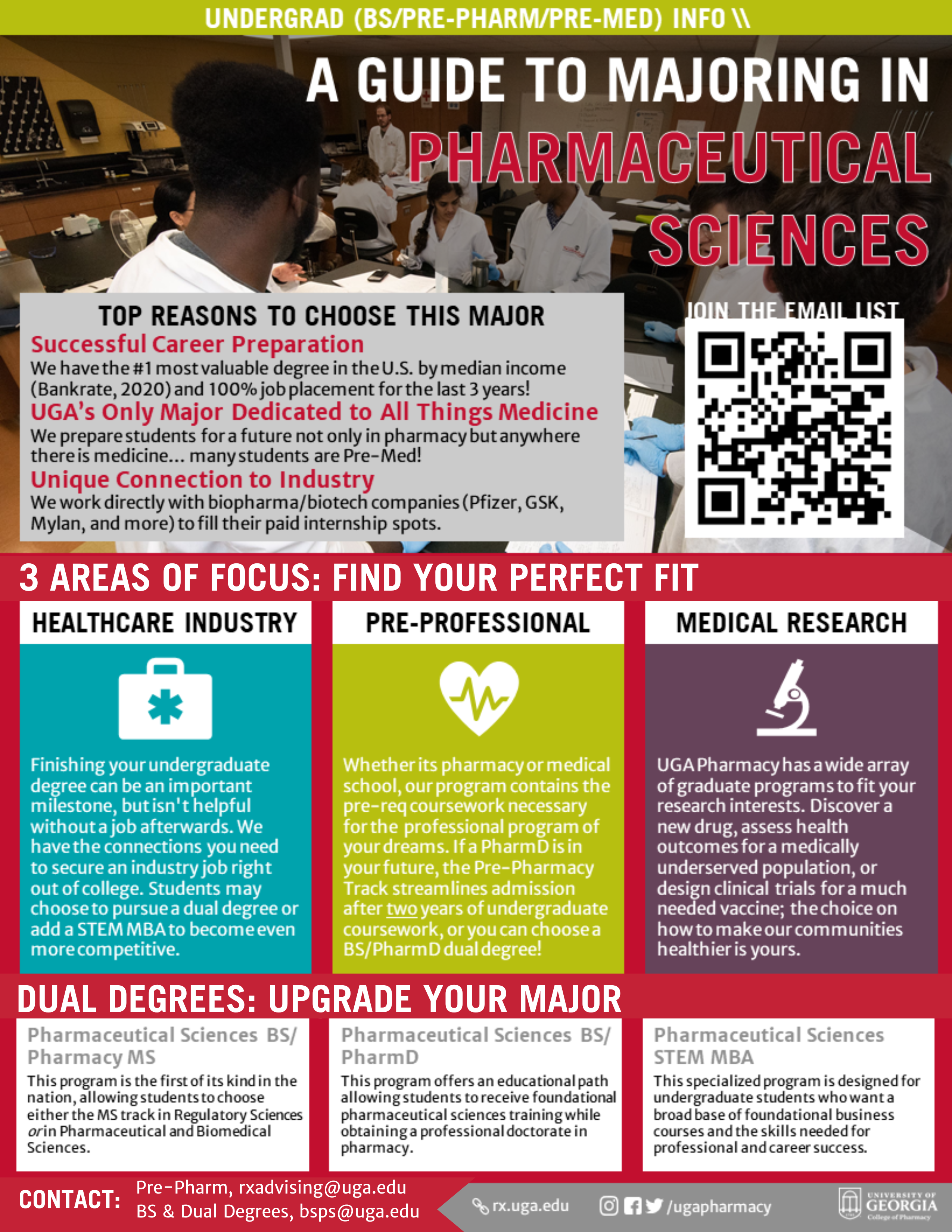

In a compelling address that bridges educational theory, cognitive science, and cultural preservation, Prof. Aderonke Soetan of the University of Ilorin has issued a powerful call to action. Delivering the university’s 295th Inaugural Lecture, titled ‘Unlocking Learning and Instructional Resources,’ Prof. Soetan urged government policymakers and education stakeholders to fundamentally re-prioritise mother-tongue instruction, particularly in the critical early years of a child’s education.

Prof. Soetan framed education not merely as formal schooling, but as the holistic acquisition of “knowledge, skills, values and habits that enable individuals to contribute meaningfully to society.” She argued that true education ‘draws out’ a learner’s innate potential—a process profoundly influenced by the learning environment and, most critically, the language of instruction. This is where the mother-tongue debate moves from cultural preference to cognitive necessity.

“Instructional resources—from models and charts to real objects and digital simulations—are most effective when aligned with the learner’s linguistic and cultural context,” Soetan explained. These tools “spark interest and unlock potential,” but their power is muted if a child must first decode an unfamiliar language before grasping the underlying concept. For example, a child learning basic arithmetic in Yoruba can focus on the logic of numbers, while a child struggling to understand the English instruction “add these quantities” faces a dual, often overwhelming, cognitive load.

The professor’s argument is supported by decades of global research. UNESCO has long advocated for mother-tongue-based multilingual education, noting that it improves learning outcomes, reduces dropout rates, and fosters stronger family and community involvement in a child’s schooling. When a child builds literacy and conceptual understanding in their first language, they create a robust cognitive framework. This framework then acts as a scaffold, making the acquisition of a second or third language—like English—far more successful and additive, rather than a replacement that can erode foundational understanding.

Soetan highlighted a crucial dual benefit: mother-tongue-based resources not only strengthen academic comprehension but also serve as vital tools for preserving Nigeria’s rich linguistic heritage, specifically naming Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba. In an era of globalisation, indigenous languages face erosion. Integrating them into the formal education system legitimises them and provides a structured pathway for their transmission to new generations.

Looking forward, Soetan connected this philosophy to modern pedagogical tools. She noted that effective teaching now leverages e-learning, virtual reality, 3D animation, and assistive technologies. Her charge to educational technologists and curriculum developers is clear: these innovative tools must be designed with cultural and linguistic relevance at their core. Imagine a virtual reality history lesson where a child explores a pre-colonial Yoruba kingdom, with narration and interfaces in their mother tongue, or a mobile app that teaches biology using locally relevant flora and fauna with indigenous language labels.

Her final appeal is a comprehensive roadmap. It requires political will to implement language-in-education policies, investment in creating high-quality instructional materials in indigenous languages, and teacher training programmes that equip educators to teach effectively in multilingual settings. The goal is not to exclude English or other global languages, but to establish a strong, culturally-grounded foundation upon which all future learning—in any language—can securely stand. This approach unlocks the true potential of Nigeria’s learners while safeguarding the nation’s invaluable cultural identity.

Edited by Kamal Tayo Oropo